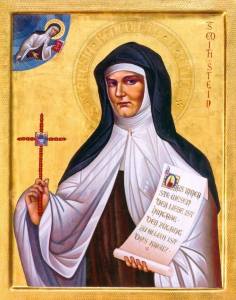

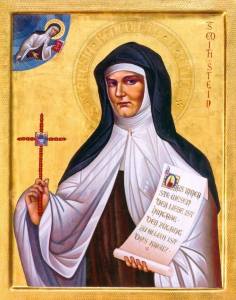

Yesterday, August 9th, was the memorial of Edith Stein, St Theresa Benedicta of the Cross. Though I make no claim to understand her, she has been close to me as a student of philosophy and as a Catholic, perhaps one of my “patron saints.” For the last 5 years or so, my email signature has included a quote by her, “My longing for truth was one single prayer”—not because I could boast of that statement myself, but because it is an aspiration I am working and fighting my way towards, with Edith Stein as inspiration, witness, and intercessor.

Edith Stein is remarkable on many counts. She was one of the first women to attend advanced studies in philosophy in Germany. She studied under Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology and perhaps the most influential philosopher of the century. Her doctoral dissertation was “The Problem of Empathy.” Though women were not awarded professorships then, Husserl put her at the top of the list. She wrote extensively on the topic of freedom, (including the essay “Freedom and Grace,” which was my first real introduction to her work), eventually realizing, as Pope John Paul II put it, that “only those who commit themselves to the love of Christ become truly free.”

Edith Stein is remarkable on many counts. She was one of the first women to attend advanced studies in philosophy in Germany. She studied under Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology and perhaps the most influential philosopher of the century. Her doctoral dissertation was “The Problem of Empathy.” Though women were not awarded professorships then, Husserl put her at the top of the list. She wrote extensively on the topic of freedom, (including the essay “Freedom and Grace,” which was my first real introduction to her work), eventually realizing, as Pope John Paul II put it, that “only those who commit themselves to the love of Christ become truly free.”

Jewish by birth and obviously versed in the Western philosophical tradition, Stein converted to Catholicism in 1922 after numerous encounters with the simple devotion and supernatural peace of Catholics and studying the faith. When she read St Theresa of Avila’s autobiography she concluded, “This is the truth.” However, her desire to enter the cloister immediately upon conversion was prevented by her spiritual advisors, which include the great Jesuit theologian Erick Pryzwara. She turned again to translation and academic work, which she now saw as a way to bring Christ and the faith into dialogue with modern thought and philosophy. Her last great work of this era was titled Finite and Eternal Being.

When the Hiterlite era began, the stay on her admittance was lifted. She entered the Carmelites in 1933 at the age of 42, later leaving her mother house for fear that her Jewish origins would threaten its safety. In 1942, she was encamped by the Nazis. There she tended to children who had been orphaned by mothers killed or mothers in shock. Those who witnessed her were astonished at the prayerful peace she maintained in a situation of utter horror and deprivation. She wrote her superior in her last letter, “So far, I have been able to pray, gloriously.” She was gassed on Aug 9, 1942, two days after arriving at Auschwitz. (Click here for a longer bio.)

When the Hiterlite era began, the stay on her admittance was lifted. She entered the Carmelites in 1933 at the age of 42, later leaving her mother house for fear that her Jewish origins would threaten its safety. In 1942, she was encamped by the Nazis. There she tended to children who had been orphaned by mothers killed or mothers in shock. Those who witnessed her were astonished at the prayerful peace she maintained in a situation of utter horror and deprivation. She wrote her superior in her last letter, “So far, I have been able to pray, gloriously.” She was gassed on Aug 9, 1942, two days after arriving at Auschwitz. (Click here for a longer bio.)

Echoing John the Baptist’s “He must increase, I must decrease,” Edith Stein said of herself, “”If anyone comes to me, I want to lead them to Him.” In her work on St John of the Cross, The Science of the Cross, she wrote, “The Crucified demands that we should follow Him.” To know the Cross is to undergo the Cross, to give up oneself for the will of God’s love, accepting every suffering, even unto death, as the birthpangs of a new creation, a new humanity created in Christ and sanctified by his Spirit. As testimony to her life of faith and sacrifice, she was canonized in 1998. On August 9th each year, the Church celebrates, not her death, but her entrance into eternal life and the witness she bears to Crucified Love for all the faithful.

*

Unpacking the statement, “to know the Cross is to undergo the Cross,” we are initially pointed in the direction of a knowledge dependent upon an experience—on undergoing the Cross. Because mysticism and its related disciplines and genres also claim the necessity of experience for knowledge, the question is what is different from the other religious ineffables, what is added by “of the Cross.” The question is, what happened on the Cross with Jesus? What is the mysterion, objectively revealed on the Cross, and how is one “initiated” into that mystery? Or again, what sort of activity and subjectivity, in the lived dimension of doing and thinking and speaking, in our freedom to decide about the totality of our being, corresponds to “receiving” this mystery of Christ on the Cross?

I can only float over a few indications to these grand questions.

The first indication, of course, is to look at the Cross. “Behold him whom they have pierced” (Jn 19:37). What happened there has a historical objectivity which can be contemplated, which must be contemplated if we are to know “who” Jesus is. The Cross possesses a depth that is infinite in what it reveals about God’s love, about the willingness of love to go to the last length to testify to the truth and save humans from sin and death. The profession of faith says: God died so we would live. Both death and life pass through the Cross, through the Crucified. To live his life (“the light and life of the world”), we must die with him his death (which destroys death).

The second indication is the call to “take up your Cross and follow me” (Mt 16:24-26). Quite a lot is entailed here, obviously—without this piece, “Christianity” is just a façade for something else, for “Christianity is Christ” (de Lubac). A more generic rephrase of the initial statement would be, “to know Christ one must follow Christ”: there is no ‘objective’ knowledge to be had outside of this following. Without following, he is an object for the intellect and learned historical or theological studies, or perhaps some hybrid philosophies. Whereas what matters is following—first and always, to receive and obey the call to love God and each other “as I have loved you” (Jn 13:34). This is a “new commandment” because, before him, we had only intimations of God’s Love; but now we see it embodied, now we have the example to imitate, the figure to hear of and hear from, to contemplate and conform ourselves to. To follow Jesus is to love as Jesus loved, to trust God as he trusted, even unto death. Now we see that that love and trust leads to the Cross. The Christoform is cruciform, inseparably (and “existentially,” not theoretically).

“The innermost essence of love is surrender [Hingabe: devotion, sacrifice, lit. “giving-in”]. The access to everything is the Cross.”

Stein’s witness and martyrdom (originally the same word) shows us what this means. She wanted to lead everyone who came to her to Him. Not only an intellectual but an embodied pointing. With Jesus,

theoria no longer matters most. “In fact, deed

outweighs word” (Balthasar). “Be not hearers of the word only, deceiving yourselves, but doers also” (Mt 7:24-27, James 1:22-25). Doing the word means following the Word, imitating what it has shown us of its substance (which includes nourishing ourselves, body and soul, on that substance in the Eucharist). Word and incarnation are inseparable, they cannot be dissected into scripture, historical figure, and some present echo, for “I am with you, even unto the end of the age” (Mt 28:20). To hear and do is to “further” the incarnation, the work of Christ, the Spirit’s plan to create a new heart in us (as promised and praye

d for: Ps 51, Ezekiel 36:26). It is to be a member of his Body, pointing to the Head. But this necessarily means “filling up in my own person whatever is lacking in Christ’s afflictions, on behalf of His Body, the Church” (Col 1:24). That is what Stein did, or it is one fruitful way to interpret her sacrifice, which began long before the camps, which indeed began with the very idea of becoming Catholic. She willed to suffer and die like the Crucified One, out of love and with love, in unity with God, to share in his hope and his life.

If I am oscillating between the objective and subjective in these notes, it is no accident. The Cross is an objective fact of revelation. So too will our Cross be objective, something we undergo. For objective also is the world’s rejection of God’s love and (even in “Christendom”) its rejection of the incarnate representative of that love, Jesus Christ (Jn 3:19, 15:18-20). But the subjective connector between “behold the pierced one” and our own (cruci)formation in Christ—well, that is the whole test, the whole issue of receiving and obeying the commandment to love as he loved, to “be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect” and all that entails—the whole ordeal of our “baptism into his death” (Rom 6:3), into the “knowledge of the love of Christ which transcends all knowledge” (Eph 3:19). Between the beatitudes, the parables, the warnings, and all the direct instructions and commands recorded of Jesus’ mouth—all interwoven with the incredible events of his life—we have quite a lot of practicable information to go on for this following, if our hearts are willing. It is also objectively attested in the witness of the saints, whom the Church raises up as exemplary imitators of Christ in each age, for they too have filled up what was lacking in his affliction and so share in the completeness of his joy (Jn 15:11, 2 Tim 2:11). But the issue is to see the total form, to contemplate the entire objective witness to his life—the life of the Son, through whom all was created, and of his mystical Body, of humanity remade in the likeness of Him. What that means for us, each of us—that is entirely a question of our own doing the following, our own “taking up” and “undergoing” our Cross so as to know it, to know Him and the fullness of that (Eastertide) life.

Having come all this way, I am surprised that I haven’t yet used the word “sacrifice” or “self-giving love” or “gift of self.” But I felt obliged to ensure such words take on the right (triune) coloring; that we learn their meaning from Jesus and his Church, not applying the concepts we already have to them. If we rephrase the initial statement to say, “To know oneself one must give oneself away out of love,” we speak the truth, we come near to the self-forgetting and surrender at stake on the Cross in a more ‘generic’ way. But what then does it mean, what does it look like, to “give oneself away out of love”? I point to the objectivity of the Cross—and Resurrection: synecdoche for and apotheosis of the whole life of Christ— to prevent the idea from getting watered down in vagueness, or from getting contaminated by human compromise and willfulness, which can creep into even the most earnest interpretation. It is evidently a statement of faith, but to believe in Jesus is to believe that the Form of self-giving love has been given to us, by very God. To know it we must see it, continually contemplate it, incarnate it in our lives. We must look at and into his wounded, Sacred Heart, until it is our heart (Gal 2:20). For God has deigned to show us something here that we could never have invented on our own. Our first task is to obey this revelation, and that means to always return to it—the Word—to see and hear ever more seriously and deeply and ‘inadvertably’ the call of the greatest love: “to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (Jn 15:13).

Edith Stein is remarkable on many counts. She was one of the first women to attend advanced studies in philosophy in Germany. She studied under Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology and perhaps the most influential philosopher of the century. Her doctoral dissertation was “The Problem of Empathy.” Though women were not awarded professorships then, Husserl put her at the top of the list. She wrote extensively on the t

Edith Stein is remarkable on many counts. She was one of the first women to attend advanced studies in philosophy in Germany. She studied under Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology and perhaps the most influential philosopher of the century. Her doctoral dissertation was “The Problem of Empathy.” Though women were not awarded professorships then, Husserl put her at the top of the list. She wrote extensively on the t When the Hiterlite era began, the stay on her admittance was lifted. She entered the Carmelites in 1933 at the age of 42, later leaving her mother house for fear that her Jewish origins would threaten its safety. In 1942, she was encamped by the Nazis. There she tended to children who had been orphaned by mothers killed or mothers in shock. Those who witnessed her were astonished at the prayerful peace she maintained in a situation of utter horror and deprivation. She wrote her superior in her last letter, “So far, I have been able to pray, gloriously.” She was gassed on Aug 9, 1942, two days after arriving at Auschwitz. (

When the Hiterlite era began, the stay on her admittance was lifted. She entered the Carmelites in 1933 at the age of 42, later leaving her mother house for fear that her Jewish origins would threaten its safety. In 1942, she was encamped by the Nazis. There she tended to children who had been orphaned by mothers killed or mothers in shock. Those who witnessed her were astonished at the prayerful peace she maintained in a situation of utter horror and deprivation. She wrote her superior in her last letter, “So far, I have been able to pray, gloriously.” She was gassed on Aug 9, 1942, two days after arriving at Auschwitz. (